Everything you need to know?

A new Special Issue of one of the leading international transport journals ‘Transportation Research A: Policy and Practice’ has just been published on the topic of Developments in Mobility as a Service (MaaS) and Intelligent Mobility. This is a valuable collection of papers that critically examines one of the areas of (future) mobility that has received much attention in recent years.

My co-authors and I (Paul Hammond and Kate Mackay) are proud to have a Reprint of our paper ‘The importance of user perspective in the evolution of MaaS’ (which first came out last year) as part of this Special Issue. At the time of its original publication I wrote a LinkedIn summary which can be found here. The highlights in a nutshell from the paper are:

1. MaaS is a promising but hyped phenomenon in its nascent state

2. MaaS by name is new but is an evolution in the ongoing pursuit of integrated transport

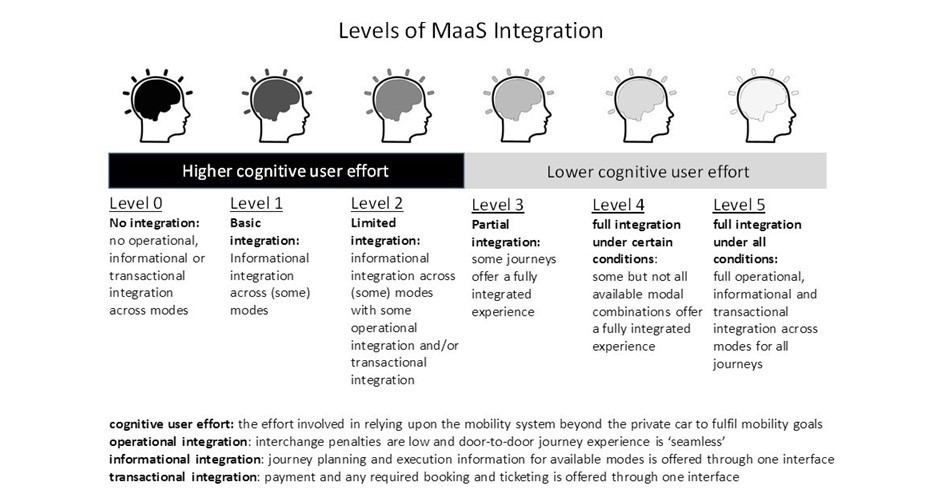

3. A taxonomy of MaaS integration (see headline image for this LinkedIn article) underlines different levels of service provision to the user

4. Users have a hierarchy of need from MaaS in which viable travel options remain key

5. Behaviour insights can inform the prospects for consideration and adoption of MaaS

In the article below, aside from highlighting the Special Issue, I offer further thoughts on the hype, substance and prospects of MaaS.

Sounds too good to be true?

MaaS seems to have moved seemingly unchallenged into the repertoire of elements we expect to form the future of mobility. By having a label that associates itself with a growing family of ‘as a Service’ propositions (e.g. Software as a Service) and drawing analogies with the approach now commonplace for mobile phone packages, MaaS can capture the imagination. It puts a menu of transport options at the users’ fingertips with the prospect of being or becoming a convenient and financially attractive alternative to the private car. Of course if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

Our changing mobility system

We experience mobility changing around us – not only in terms of our own changing lives and behaviours over time but in terms of what is on offer. Go back a couple of decades and the world of Google Maps, smartphones, ridehailing apps, e-bikes, cycle share schemes, e-scooters and more besides was not available as it is today. Go forward a couple more decades and who knows what else will have changed. In this context, MaaS is not just about how we access and consume mobility but also about changing forms of mobility that are used.

What really matters in MaaS?

This raises the question of what we even mean by ‘MaaS’ – when is a mobility offer a form of MaaS and when isn’t it? This is partly why, in our paper, we set out a taxonomy called the ‘Levels of MaaS Integration’ – because the answer isn’t binary. We see MaaS taking multiple forms and notably including forms that existed way before MaaS as a term was coined. Indeed, we refer to MaaS as the mobility system beyond the private car. In this system, the MaaS intermediaries – the organisations that aim to offer brokerage services as an interface between what mobility services are on offer and the user wishing to gain access to those services – are, we suggest, high up in the users’ hierarchy of need. Users’ more fundamental needs concern there being viable and attractive alternatives to the private car. This is not rocket science conceptually and is readily understood by behavioural researchers and transport planners. At the heart of the success of MaaS is not the new app on our phone but the availability of means of travel that we find satisfactory if not appealing to use: walking, cycling, buses and trains as well as the newer variants on these.

Knowing easily what is on offer

There is an important role for information in helping to ensure that the choice sets we are aware of when making travel decisions include all viable modes that exist in practice. If an improved frequency of bus service with new well-designed vehicles is in place but we have not learnt about it then we may still be in our cars picturing our perception of bus travel based upon an outdated poor experience. Here, the digital connectivity of the 21st century can more readily bring such changes to our attention in a way that, increasingly, limits the cognitive effort required of us to ‘do the homework’ on our travel options. However, let’s not be naïve enough to think that we are all behaving like Mr Spock in making our travel choices. For most people, most of their time their journeys are local, routine and familiar – they have determined the means of travel that suits them well enough and are happy to stick with it. They are more akin to Homer Simpson – who has more important things to occupy his mind (Duff beer, doughnuts, and sleep) than to worry about optimising his journey to work –‘good enough’ is just fine thank you.

Its about evolution not revolution

It should come as no surprise then that if a new ‘Mobility as a Service’ offer is introduced, apart from trial volunteers who may have quite specific reasons for joining the trial, there is unlikely to be a revolution in behaviour with people clamouring to take advantage of the offer. Many people will be unaware of it, aware but disinterested or aware but unclear how to make sense of what is on offer and whether or not it is going to be something to invest time and effort in embracing. Yet at the same time, an evolution of MaaS and in turn of changing travel behaviours is quite evidently happening and will continue to unfold over time. Love it or loath it, Google Maps offers a MaaS ecosystem that has been evolving over time – as a familiar brand, founded upon the power of geography, it is something many people turn to for a growing number of purposes, including different travel options – car, bus, tube, train, plane, walk, cycle, scooter.

Is there really a viable business model?

In separate thinking on Walking as a Service I suggest that there is a business model founded upon selling access to geography. Google Maps Navigation is free at the point of use and helps users avoid getting lost and know how far it is to walk and how long it will take. Its giving them access to geography. Businesses have a vested interest in being part of that geography to draw themselves to the attention of prospective (passing) customers. They put themselves on the Google Map which in turn helps provide landmarks for the individual on their walking trip. Meanwhile, Google is of course monetising this undertaking through ‘click bait’ and advertising revenues. Elsewhere, the business model of MaaS seems to be founded upon selling access to mobility. The latter is currently struggling to clearly demonstrate its viability. The former seems to be thriving and indeed the Google model of MaaS may well overwhelm other MaaS models and be the epicentre of future development as it brings mobility and geography together.

Some closing questions

If you’ve got this far through reading the article – thank you! But more importantly, what did you make if it? Are some of the assertions new to you? Have they challenged your own thinking? Do you disagree with some of them? I’d be really interested if you are willing to share your views by offering a comment or two.

To close I’ll leave some questions hanging:

1. Is there a straightforward definition of MaaS or does it mean different things to different people?

2. If the term is ambiguous or an umbrella for a number of different things, are we at risk of misunderstandings and talking at cross purposes in professional debate and policy and practice?

3. Is there enough constructively critical examination of MaaS and its prospects or are we still at risk of being seduced by MaaS advocacy?

4. How much untapped behaviour change might there be that has the potential to be unlocked by adding ‘MaaS’ to the existing mobility system beyond the car?

5. Will MaaS be able to break out of an orbit around the car (hired or ride hailed)?

Leave a comment