In this short article I reflect briefly upon views in the transport sector regarding the prospects for decarbonisation by 2050.

Polling

As members of CIHT will know, each month the CIHT 100 panel is asked a topical question. In this month’s members’ magazine the question was: “Will the transport sector be able to meet the Government’s target of achieving net zero emissions by 2050?”. The responses were as follows:

YES: 44% – “Good progress has already been made in terms of advancing technology for green vehicles. New working patterns will also reduce the need to travel.”

NO: 56% – “There are too many factors which Government cannot control. People need to travel less overall and take more public transport. Aviation has a long way to go.”

Elaborating on the topical question were Matt Tooby (Client director, highways, Atkins) in the YES corner, and Jillian Anable (Professor of transport and energy, University of Leeds) in the NO corner.

Matt is filled with great optimism, sensing collective ambition in the highways sector with one of the driving forces being technology. Jillian believes we have no chance, pointing to a sector with emissions higher now than in 1990 and with less than 1% of cars and vans on our roads running purely on electricity.

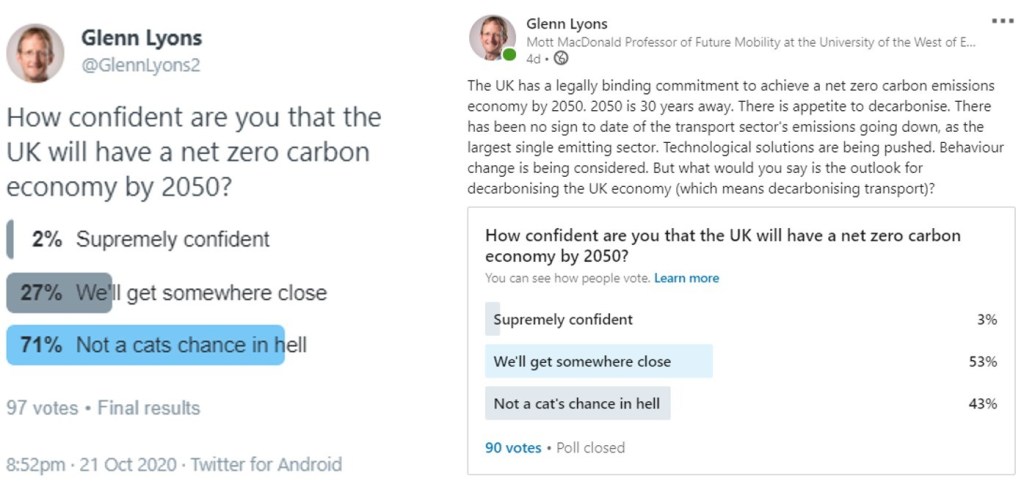

I was curious. Last week I asked a similar question on Twitter and LinkedIn, via a 24 hour poll (focused on the whole economy but with the implication being that transport was the make or break sector). The results are shown below. Very broadly speaking, professional opinion is at best divided but leaning towards having little faith in our ability to rise successfully to the challenge before us.

LinkedIn comments included the suggestion that electrification of fleets would happen too slowly and that current policies and actions were insufficient, with behaviour change only scratching the surface. Meanwhile there was also a reminder that “People overestimate what they can do in one year and underestimate what they can do in 10“.

Diffusion of innovation

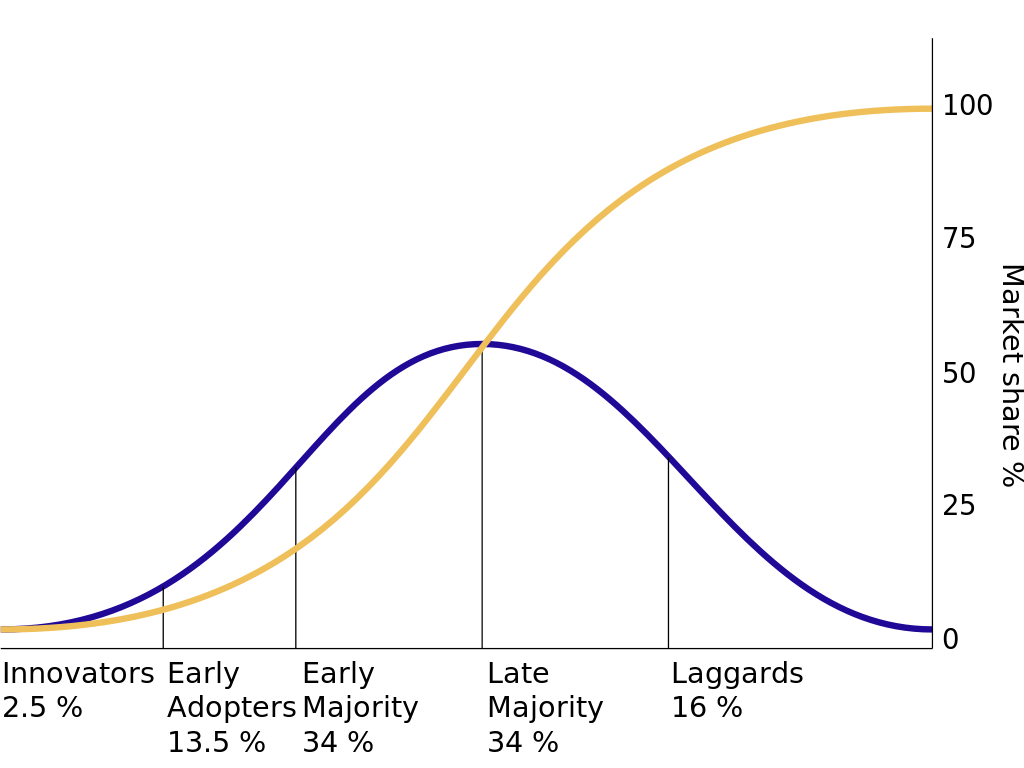

I found myself thinking about the Diffusion of Innovation – see below.

According to the Global EV Outlook 2020 from the International Energy Agency, electric cars accounted for 2.6% of global sales or 1% of global car stock in 2019. ‘Electric cars’ includes plug-in hybrid electric vehicles as well as battery electric vehicles (two thirds of the world’s electric car fleet is battery electric). This suggests that when it comes to electric cars we are barely moving out of the Innovators phase of innovation diffusion into the Early Adopters. Notwithstanding Government plans to bring forward from 2040 its ban on sales of new petrol, diesel and hybrid cars, its important to be reminded that not all innovations fully diffuse to achieve 100% market share.

Battery electric addresses removal of the direct (‘tailpipe’) emissions from a vehicle but does not address the embodied carbon in the vehicle – that emitted as a result of manufacturing the vehicle. Cars, taxis and light vans together represent around 70% of direct emissions from UK domestic transport. Reduction and removal of direct emissions from buses, coaches, heavy goods vehicles, (domestic) shipping, and (domestic) aviation is also required. There are multiple s-curves – and Technology Readiness Levels of solutions across modes are highly varied.

Hype cycle

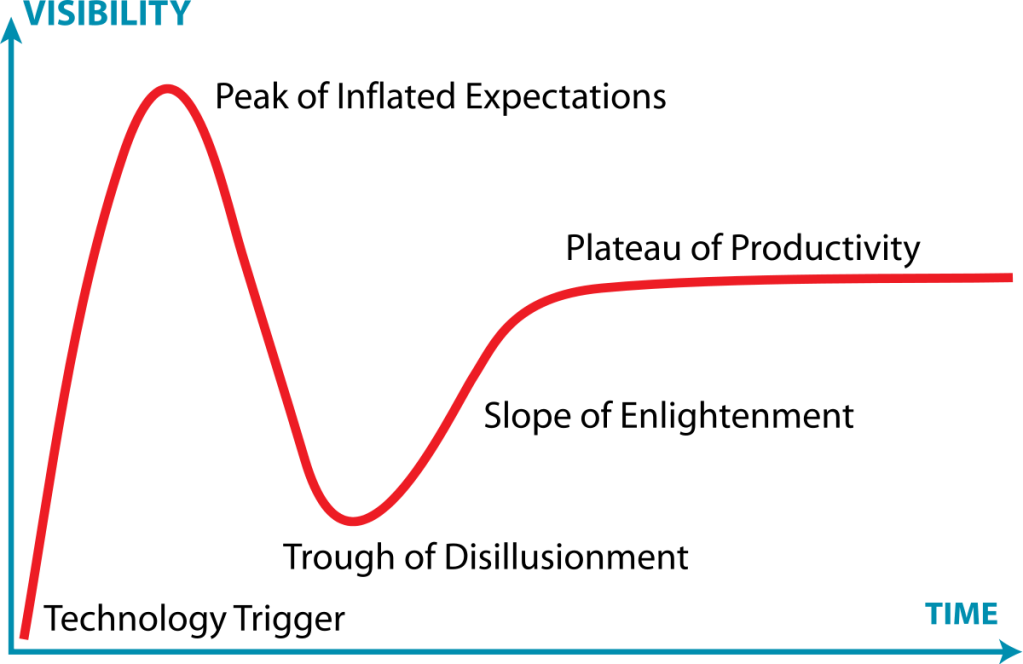

As well as s-curves, there is the hype cycle to consider:

The transport sector seems especially enamoured with ‘technology fix’. Whether looking for problems, or born out of a strong need for a solution to a problem, technology-based solutions seem to have a habit in the transport sector of following the hype cycle – think ‘driverless cars’ or, I would suggest, Mobility as a Service. In this light, when we are presented with bold commitments for, and artists’ impressions of, zero emissions vehicles that are not yet commercially available, we should pay heed to the hype cycle and manage our expectations accordingly.

Velocity of change

I’ve had the privilege of being part of a team developing a series of technology roadmaps for DfT for the removal of direct emissions from UK domestic transport by 2050. You can see a 7-minute talking head video about this that was included as a contribution to the DfT’s workshops over the summer this year as part of preparing its Transport Decarbonisation Plan. Having had the chance to take a close look at the challenge before us, I am only too well aware of the punishing schedule, degree of public and private sector commitment, and consumer appetite that will be required to achieve multimodal transition away from fossil-fuel powered vehicles in a period of only three decades. At the heart of the matter is what I refer to as the “velocity of change” – a combination of the direction of change and speed of change. There are competing solutions for decarbonisation. This does mean we have a Plan B (and perhaps Plan C) if Plan A isn’t sufficient. On the other hand, if attention is divided between progressing Plans A, B and C then this may slow us down. We don’t have time for delay – we need to move at great pace in a direction that can deliver a successful solution.

Optimism bias

The polls at the start of this article can only be indicative of collective professional or expert judgement but they are likely to reflect a combination of optimism, pessimism and realism. Each of us can judge for ourselves where we stand individually and why. It is worth noting, however, that we are all likely to be subject to unconscious biases in the formation and expression of our views. The Behavioural Insights Team in its report for the DfT, considered such biases, including most notably optimism bias – “we tend to overweight our odds of success, and underweight our chances of failure”. Bent Flyvberg is well known for his critical examination of this bias. It is formally recognised as a bias by the DfT in its appraisal guidance.

I’m left wondering to what extent as professionals we are calling out optimism bias and to what extent transport authorities are factoring it in when it comes to decarbonising transport?

A personal view

I want us to succeed. However, to do so, we need to ensure we are sizing up the challenge before us and accounting for the issues above in determining what needs to be done, what timetable is required and what resources are called for.

My personal judgement is as follows:

- There is now an unprecedented intent and effort to decarbonise transport.

- This intent and effort is being given increasing visibility in the media.

- Expectations are being raised, especially surrounding technology-based solutions.

- In spite of intention and effort to decarbonise being relatively high, optimism bias is distorting an ability to distinguish between relative and absolute intent and effort. Absolute intent and especially absolute effort is falling short of that required to achieve decarbonisation of transport by 2050.

- A least regrets approach means that efforts must be redoubled to counter optimism bias.

- Such efforts apply not only to addressing direct emissions through technology but to addressing better planning affecting people’s travel demand, and addressing measures to significant influence travel behaviours and reduce our reliance on motorised transport.

- Any notion that greening business as usual will be sufficient is misguided.

I’m not sure whether or not we have the means to succeed but our greatest threat is complacency. Decarbonising transport by 2050 will require unprecedented resolve and a sustained sense of urgency. As my colleague has put it, we are in a marathon that consists of a series of successive, unrelenting sprints.

Leave a comment